The Acorn Fire was well on its way to burning out 26 homes near Markleeville when I got a phone call from a forest service dispatcher telling me that the Stanislaus Hotshots had left Mi-Wuk Village on their way to the fire. It was about 2:00 p.m. on Thursday, July 30, 1987. By the time I got reporter Michael Winters it was dark as we headed up Highway 4 toward Markleeville. In addition to the darkness, I didn’t have the correct radio frequency so we headed to fire camp in Minden, Nevada to locate the crew. After some confusing exchanges with the incident command team, we found out the Stan Shot crew had been doing some freelance burnouts and were coming back in to eat and get an assignment for the next day.

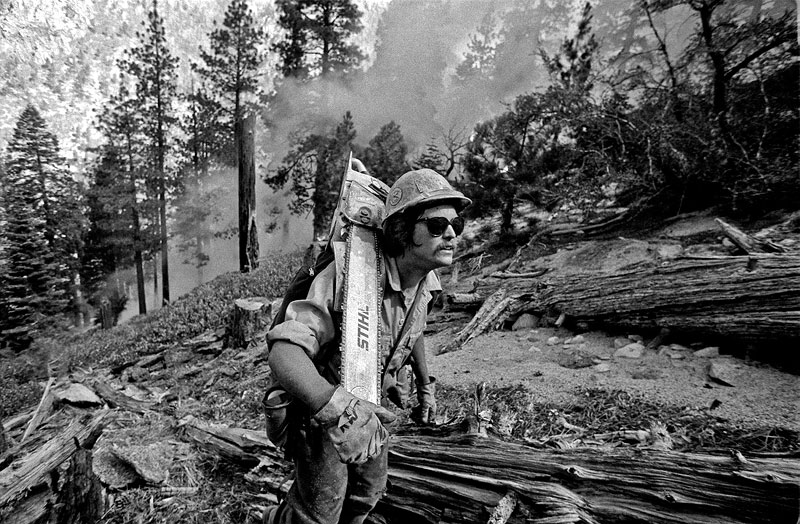

The next morning, we went with the crew into the Toiyabe National Forest. We were at about 5,800 feet elevation when we got out of the crew buggy. This is where Sup 20 Greg “Rax†Overacker took over. Rax took command of a strike team of shot crews and instructed us to climb up a 1700 foot ridge to start cutting fire line. I got my best image of sawyer Kevin Wallin hiking up the ridge at about 6,500 feet.

It all started with this photograph I took the year before. Early June 1986, Bob White, the Sonora Bureau reporter for The Bee, and I did a story on the Stanislaus Hotshots getting ready for the fire season. The Stan Shots were based at Mi-Wuk Village. In his office, I asked Overacker what was the difference between his crew and a regular crew. He said it was how much fire line they could cut per hour. So we headed to a very steep hillside near Tuolumne City and they started cutting a firebreak. I ran uphill on the other side of the road and shot this image with my 300mm lens. Then I ran up and down the firebreak while the crew was cutting. I didn’t know that Racks and the crew were impressed that I hustled around to make a good image. To me this was normal.

After my promotion to Chief Photographer in 1980, I inherited the intern program. As part of briefing interns I would require them to a make a list of assignment ideas that they might want to make a special project during their internship. I would always offer the idea of spending time with a wildland fire crew and going with the crew to a fire. Fast forward to 1987 and Bob White is an assistant metro editor. Bob talked the Forest Service and Greg Overacker into the great idea of me doing a story on the Stanislaus Hotshots.

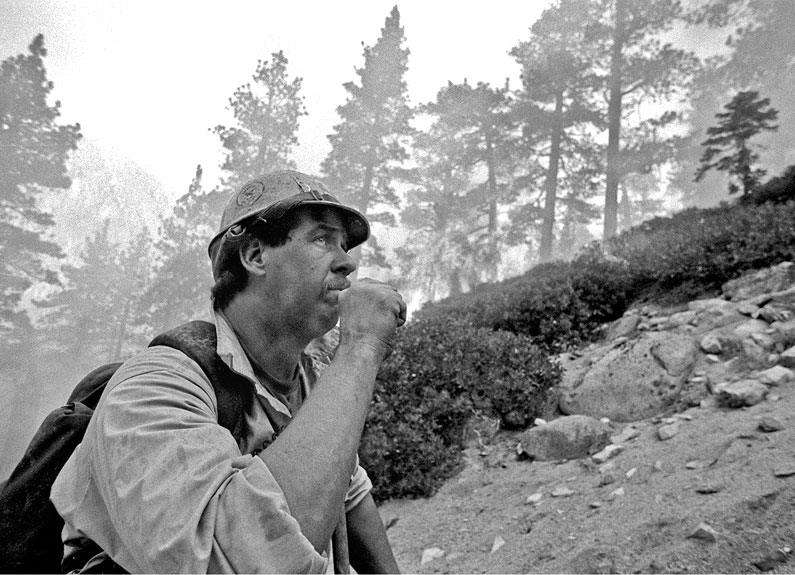

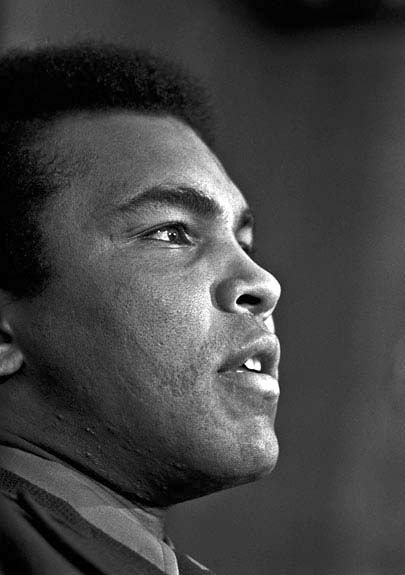

Half way up the ridge firefighter Turpin from Coulterville takes a moment out of the smoke and blaze before hiking to the top of the 7,600 foot ridge.

I witnessed the Incident Command System (ICS) first hand. By the time we reached the location to cut fire line, Rax was supervising the air attack. One of the Stanislaus Hotshot fire captains was the Division chief and the other was the Strike Team leader. The squad bosses were running the crew. Each promotion earned the firefighter an increase in pay and was noted on their time cards.

Sup 20 talked to an air tanker and the next thing I knew we had pink dots all over us.

Firefighters cutting a fire line before the active head of the fire got to their position.

The first night we ate at fire camp in Minden, Nevada, and slept in sleeping bags on the open ground.

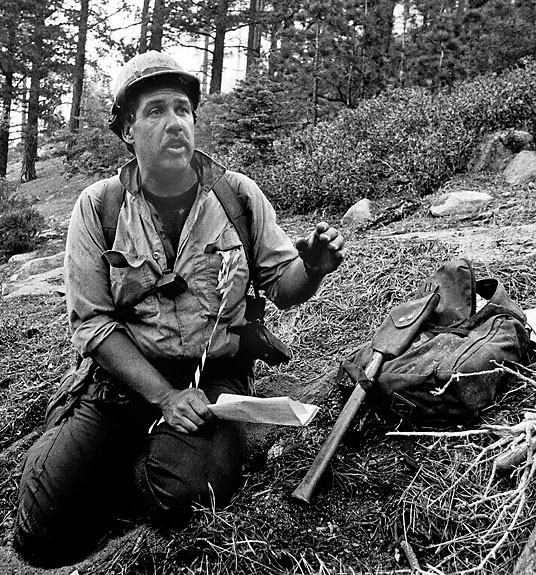

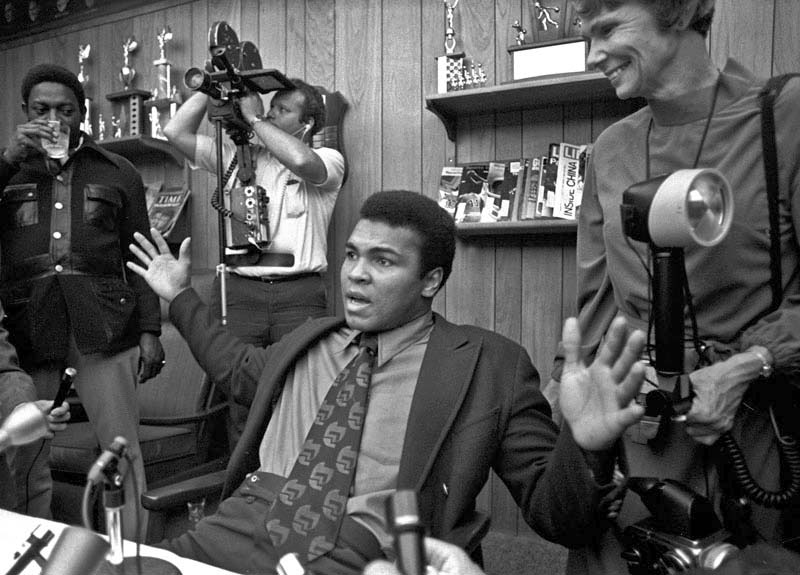

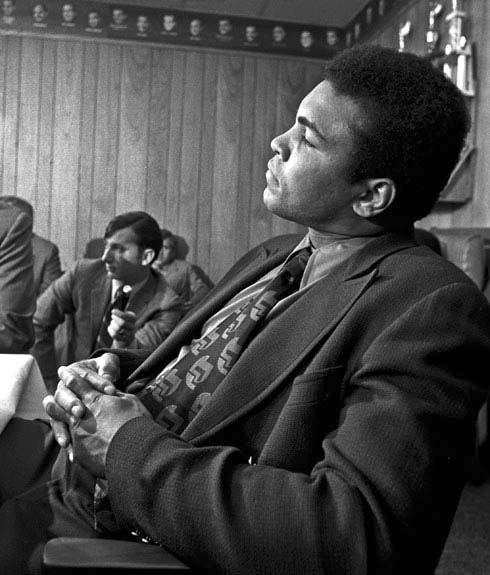

Members of the Hotshot crew listen to what Overacker had planned for the next day.

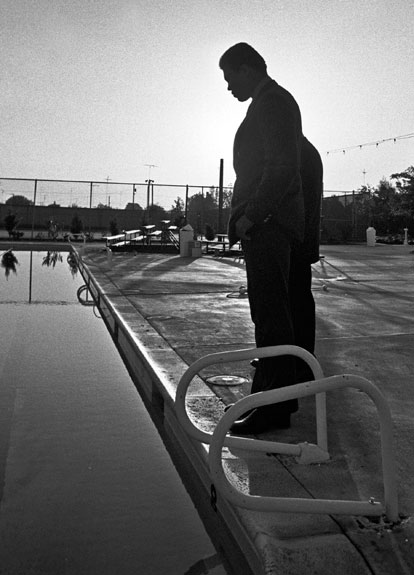

Rax observing fire while he was Air Attack Chief. The ICS is lined out in the Fireline Handbook. I learned so much from this experience. Unknowable at the time was the fact that there would be another fire in 1987 during which I would put my newly acquired knowledge to use.

I was surprised that after breathing smoke all day a crewmember would want to smoke a cigar.

Crew picture before we headed out for dinner.

Sacramento Bee photographer Dick Schmidt photographed me at the bottom of the hill before we headed up. He was surprised to see me and had tons of questions, but I had to go. Thanks, Dick, for sending me this transparency.